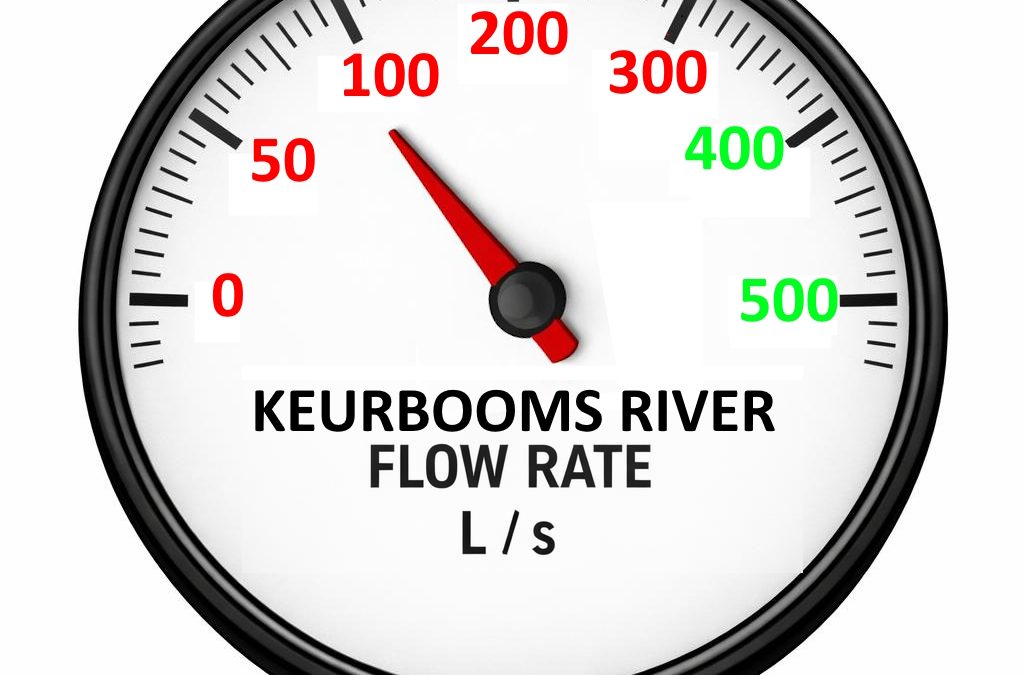

Bitou’s water crisis has unfortunately reached a new dimension: The reported flow rate in the Keurboom’s River keeps on dropping and is now way beyond the – already lowered – minimum of 150 liters/second. Level III water restrictions imposed by Bitou Municipality in December 2025 had already limited the water usage per household to 15 kiloliters/month. On 7 January 2026 permitted water consumption per household was then further reduced to 10 kiloliters/month. The Municipality’s relevant statement mentioned that “more stringent water restrictions will be announced shortly” and that the Keurbooms River had dropped to 90 litres/second, the Roodefontein Dam level was at 37.78% and that “Abstraction from Keurbooms River (has been) halted”, read: no more water was pumped from the river to the water treatment plant.

On 12 January another drop in the Keurbooms’ flow rate was then reported, now bringing it down to 76 liters/second. What Municipality did not mention though was that the flow rate measured on 10 January at 12:36 noon had in fact already been down to half of that: 36 Liters/second! Be this as it may, with no water being pumped from the river more had to be taken from the Roodefontein dam, bringing down the level by 6.78 % to 31 % in the course of just 2 days.

This is a crisis that has long been in the making, and it started taking on dramatic proportions long before the 2025/2026 holiday season. Here’s why:

Where does our water come from?

With the exception of the comparatively few households relying on an independent water supply (e.g.: rain tanks, boreholes etc.) all of us are dependent on Bitou’s bulk water infrastructure. The moment you open a tap you therefore draw water that has been pumped, stored, treated and supplied to you via this municipal water infrastructure. The maximum amount of water this infrastructure can deliver to our taps depends in the main on two factors:

- The total amount of untreated water that can be made available to the water infrastructure at its point of entry, and

- the size and operating performance of the bulk infrastructure (e.g., state and size of storage facilities and treatment plants; efficiency of pumps; distribution network/pipes; water loss through leakages; water management expertise and workforce; planning and maintenance etc.).

In a long-term strategic perspective these two points must of course be addressed in combination (if you want to learn more about this we suggest you read the very informative Plett Ratepayers Association’s “Annual Water Report” for 2025).

If you’re a user of the Bitou water infrastructure then over 80 % of the water that you draw from your taps over the course of a year will have come directly from the Keurbooms River. Here is the breakdown of the Bitou water infrastructure supply sources for 2024 (data provided by the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS)):

| Water source | Keurbooms River Extraction | Roodefontein Dam | Desalination Plant | Total |

| kiloliters per annum (2024) | 4 125 827 | 737 946 | 24 969 | 4 888 742 |

| % supply | 84% | 15% | 1 % | 100 % |

So the Keurbooms is clearly our number one water source. But there’s a limit on how much water can be extracted from it – a limit measured not in terms of how much you take out, but in terms of how much water has to remain in and flow down the river. This is called the “flow reserve” – in other words, the amount of water flowing that is necessary to keep the Keurbooms eco-system healthy (more on that further down). This amount is measured at the weir below the pumps, in liters per second. The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) has established that this minimum flow reserve for the Keurbooms should be 300 liters/second. We’ll come back to that point in a second…

What about Roodefontein Dam?

The amount of water coming down the Keurbooms does of course vary: Good rains in the catchment area will result in a strong flow; a prolonged period of drought will do the opposite. The Roodefontein Dam serves as Bitou’s main storage facility that acts as a buffer against the fluctuating river water supply. For example, in February 2024 more than 50% of the water required had to be taken from the dam because of a weak flow rate, whereas in May 2024 the Keurbooms alone supplied water to the infrastructure, allowing the dam levels to rise again.

However, there is of course also a restriction on how much water can be taken from the dam which at 100% holds 2 million kiloliters. Municipality’s legal allocation of water from the dam is roughly 306 thousand kiloliters per annum (an amount which the Municipality had already exceeded for the 2025 year by 24th November 2025, according to information provided by the DWS). Whatever the annual allocation, Bitou Municipality may in any event not draw down the dam any lower than an absolute minimum of 555 thousand kiloliter capacity or 27%. On 7 January 2026 Municipality reported a dam level of 37.78 %. This means we were left with a 10% final buffer = 200,000 kiloliters. On 12 January it stands at 31 % – 4 % or 80 000 kiloliters left. The maths is straightforward:

Assuming that the current drought conditions will not ease significantly before end-February 2026 there is still a one and a half month period where dam water will be needed to serve as raw water supply. Based on the 2024 figures the water demand for the period mid-January to end February 2026 will amount to a total of approx. 180.000 kiloliters. With only 80,000 left we are thus 100,000 kiloliters short – there’s simply not enough water to be taken from Roodefontein Dam to meet Bitou’s projected demand.

As for the desalination plant, its maximum capacity is 2,000 kiloliters/day. If run non-stop at full capacity, the plant could thus theoretically produce 60,000 kiloliters/month. But feedback from the DWS indicates that it is unlikely that this can be done: Not only is the running of the plant extremely expensive; we also do not know if the plant can technically handle the required load over a prolonged period. Be this as it may, historical data from 2024 recorded a maximum output of 12,250 kiloliters/month in February of that year. Almost double that amount would now be needed.

So we’re essentially back to the Keurbooms River, right? Well…

We’re already beyond the limit: No more water extraction from the Keurbooms River for now

As explained above there is a limit to how much water Bitou Municipality is allowed to pump from the Keurbooms – the so-called “flow reserve” of 300 liters/second. This limit had already been lowered by the DWS in view of the excessive water demand over the holdiday period in December 2025, reducing it to 150 liters/second. But the situation has worsened since:

On 5 January 2026 the flow rate of the Keurbooms dropped below 100 liters/second. On 7 January it dropped below 90 liters/second. This is clearly lower than the already reduced 150 l/s from the required 300L/s flow reserve, as per the DWS abstraction condition.

The consequence: All abstractions from the Keurbooms – municipal and farming – must now cease with immediate effect, and only the Roodefontein dam, boreholes and the desalination plant may be used, until the river’s flow rate has increased again above the set threshhold.

Why bother about the Keurbooms flow rate?

The Keurboom estuary and lagoon is one of South Africa’s most valuable eco-systems, ranking among the top 18 estuaries in our country in terms of ecological importance. As a system the estuary depends to a large degree on the fluctuating water levels, and the constant exchange between sea water with a high level of salinity, and sweet water collected upstream in the Keurbooms catchment area.

If the flow rate drops below the critical level, the supply of river water will no longer match the amount of sea water that flows upstream on high tide. As a result, the level of salinity in the river will rise, the risk being that it might rise above the level that is tolerable for plants and animals there. Moreover, because of the lower flow rate the river can no longer transport mud and debris to the mouth; it will begin to silt up.

For a detailed description of the grave risks and consequences see this Facebook post of 07 January 2026 by Keir Heynes on “Plett in Stereo”, titled THE BITOU WATER CRISIS: ON THE ECOLOGICAL RESERVE OF THE KEURBOOMS AND WHY ABSTRACTION LIMITS EXIST.

Here is an aerial picture of the mouth of the lagoon taken on 5 January 2026, shortly before low tide which documents the risk (Photo courtesy of Anton Miller).

Why does the flow rate of the Keurbooms River drop?

There are four major factors that can lead to a dramatic reduction in a river’s flow rate:

- Significantly lower rainfall in the catchment area due to seasonal patterns, nowadays often compounded by climate change and/or drought conditions

- High-level infestation of the catchment area with AIS (alien invasive species) vegetation. Compared to indigenous vegetation, AIS species consume an excessive amount of water which will then no longer reach the river.

- Manipulation of the river’s normal flow rate by uncontrolled building and usage of dams and weirs.

- Excessive water extraction by pumping or channelling water from the river for irrigation and/or water storage purposes.

How much water does Bitou need for human consumption – and how can the shortfall be addressed?

Simply put: we certainly use too much water in terms of our current water supply infrastructure – and that problem will get worse with more development taking place. While the Keurbooms can in principle at current supply enough water for about nine months of the year measures to safeguard the resource for the remaining three months must to be taken. The options under discussion are

- to increase storage and/or pumping capacity for the Roodefontein Dam, by e.g. constructing a new pipeline from the Keurbooms to the Roodefontein Dam (the approach favoured by the Department of Water and Sanitation);

- to construct an additional storage dam (the approach favoured by the Plett Ratepayers Association);

- to increase the river flow in the longer term by dealing with the massive AIS infestation of the Keurboom catchment area.

Unfortunately, the third option – which has been brought to the attention of the Municipality and the Ratepayers Association repeatedly by the Forum – has received little attention to date. This is despite the massive potential benefit that could be realised with the added benefit of providing work to the local communities.

The benefits of AIS clearing: up to 30 % increase of the Keurbooms River flow per annum

The total catchment area of the Keurbooms River extends over 86 000 hectares. When you explore the Keurbooms by canoeing up the river from the N2 bridge you will soon paddle in one of the most spectacular gorges and enjoy the views onto the steep cliff faces with lots of indigenous vegetation.

Unfortunately what we encounter here is perhaps one of the last stretches of this river that is not heavily infested with alien vegetation. On 11 January 2026 we drove up the R339 and made our way down to the river about 5 km before the turnoff to Diepwalle. Here alien vegetation abounds, including forests of Eucalyptus, some of them up to 50m tall. A 3-year-old Eucalyptus might use 20 liters/day, while a 20-year-old could use 200 liters/day – and up here there are literally tens of thousands of them, plus Black Wattle and other aliens. We found the river to be extremely shallow at present – the combined effect of the drought and the AIS infestation of the catchment.

The Swiss CABI research centre informs that “the invasive Eucalyptus species in South Africa are responsible for the loss of 16% of the 1,444 million cubic metres of water resources lost to invasive plants every year.” Apart from being extremely thirsty trees, they also produce a lot of biomass and are therefore a serious fire risk. Clearing alien invasive species (AIS) in the Keurbooms River catchment area would therefore increase the river’s water flow by reducing transpiration losses from invasive plants like eucalyptus and black wattle. Specific measurements in comparable contexts show gains of approximately 1,776 cubic meters per hectare cleared annually. One documented AIS clearance project cleared 141 hectares, freeing 250,000 m³ annually. Moreover, these gains primarily boost low and mid flows during dry seasons – which is when the current shortages occur.

Elsewhere in South Africa, local monitoring has observed dramatic flow increases post-clearing, with some streams reviving after drying up. General South African studies indicate AIS removal can boost streamflow by 15–30% in invaded catchments, with riparian clearing doubling benefits. The Keurbooms catchement’s area median annual rainfall is around 144 million m³/year, so even partial clearing would yield meaningful gains of up to 50 million m³ a year.

What about the cost of an AIS clearing programme? Is it feasable?

Clearing the 86 000 hectares of the Keurbooms catchement area would certainly require lots of money. Moreover, it would be a complex undertaking, considering the number of stake holders and landowners. In March 2025 Plett Environmental Forum put together a discussion paper that addresses these issues, looks at the pros and cons of an AIS clearing program in terms of a cost/benefit comparison and outlines the steps that would need to be taken for a more thorough evaluation.

Remember though that AIS clearing is not just about water and biodiversity. It also significantly reduces the chances of uncontrolled wildfires that keep on threating our communities. For an analysis of costs and feasability of AIS clearing in a multi-dimensional perspective see the work of Dr. Guy Preston, previous Deputy Director-General: Environmental Programmes of the Department of the Environment and Agriculture who presented on this topic inn Plettenberg Bay in June 2024. You can download Dr. Preston’s presentation here. And last not least: a co-ordinated AIS clearing program would create employment opportunities in Bitou, combining the eco-logical with the social benefit which research papers on the topic regularly highlights (see eg. Le Maitre et.al, Invasive alien trees and water resources in South Africa: case studies of the costs and benefits of management. In: Forest Ecology and Management 160 (2002) 143–159).

The bigger picture: A crisis in the making since the early 2000s …

It would be short-sighted to address Bitou’s water shortage as a mere supply problem that can be solved by an engineering solution. Rather, an integrated view should be adopted to look at the systemic mismatch between a limited supply and an ever rising demand. For how and how much water we consume is certainly part of the problem…

Also, the current situation has not arisen overnight – it has long been in the making. For more information and links to various relevant scientific reports on the imminent water crisis that were drafted since 2005 please see the page Challenge #1: Water Supply